The Biennale di Venezia has just opened and the world's critics, journalists and (connected) collectors descended on the lagoon to sample the latest in contemporary art.

The American presence, at the Biennale as all too often on the world stage, is heavy handed. According to the curator, Lisa Freiman, "The main theme of the project is looking at the U. S. pavilion as a site of international competition" (New York Times online, 16 March 2011). The artists, Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla, created six works to focus attention on the way in which the Biennale itself is enmeshed in international competition -- not only cultural but military, athletic, and corporate. But that debate, as we suggested in our first dispatch, is largely moot, with many countries' pavilions now hosting artists from other countries, and so many other nations' artists exploring avenues of cooperation, rather than competition, that the U. S. comes off as out of touch. The loud and ominous rumble of a Korean war-era tank, here converted into an exercise treadmill "running" on the energy created by an athlete, can be heard in nearly every corner of the Giardini. For the U. S. to impose the sound of a military weapon on any gathering of nations is to these reporters' minds extremely unfortunate. Conceptually an intriguing idea -- but oppressive in reality.

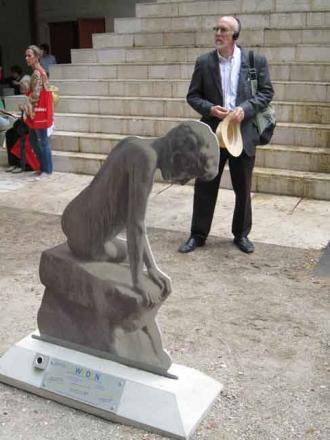

Fia Backström. Borderless Bastards (Sweden).

Digital photo on metal. 2011.

Photo: Marjorie Och

One artist who sought cooperation while focusing on national identity is Fia Backström. This New York-based Swedish artist's project was predicated on persuading other artists to let her install photo reproductions of national sculptures near their pavilions. Each had an infra-red triggered sound recording of local 'cultural producers' talking about the stereotypes of their countries' national identity -- sunshine and antiquities for Greece, IKEA and soft porn for Sweden, and so forth. Not all the artists were cooperative -- Serbia's representative, Raa Todosijevic, thought Backström was overreaching in asking to "share" his space, but most apparently went along with it.

Sigalit Landau. Salt Bridge over Dead Sea.

Drawing on photograph. 2011.

Photo: Marjorie Och

One of those was Sigalit Landau, who not only gamely invited Backström to site a work outside the Israeli pavilion, but also radically reorganized the space within, including knocking a large hole through a wall to accommodate a complex network of fresh and salt water pipes. These act both as a metaphor for the human circulatory system and reinforce Landau's focus on the Dead Sea as a possible point of cooperation between Israel and its neighbors. A particularly poetic image (and possible future project) is Landau's vision for a salt bridge linking Jordan and Israel across the Dead Sea. Like the little girl in her video, tying together the shoelaces of adults sitting around a negotiating table, Landau is mischievous but insists on being taken seriously in demanding urgent attention to the region's water issues.

Christian Boltanski. Be New.

Computerized videos. 2011.

Photo: Marjorie Och

Christian Boltanski's installation at the French pavilion, featuring hundreds of faces on long rolls running through the space, reminded Preston of a blend of Claude Leveque (who filled the pavilion in 2009 with a similar metal framework) and Simon Starling (who created an absurdist device that projected a film about the metal shop where the device was constructed).

Marjorie had a different take on it, emphasizing Boltanski's computerized exquisite corpse-cum-Vegas slot machine "wheel of fortune" that combined sections of faces of Polish babies and elderly Swiss to create over a million possible combinations. Pushing a button froze the images, and if you lined up all three parts you won something. You can play at home at www.boltanski-chance.com. The element of chance in the production of any "face" foregrounded for both of us the infinite interpretations of contemporary art. Boltanski's space could also be read as an imprisoning and claustrophobic environment both for those mechanically produced by it and for those experiencing the world he creates.

Thomas Hirschhorn. Crystal of Resistance.

Mixed media installation. 2011.

Photo: Marjorie Och

Lastly, the sharp good humor of Thomas Hirschhorn was in full glory at the Swiss Pavilion. Hirschhorn used the most mundane of materials -- including his favored aluminum foil, cotton swabs, and brown plastic packing tape -- to create a riotous Merzbau-like environment that was part funhouse and part crystal cave fantasy. At close inspection, the wildly colorful appearance of Hirschhorn's work revealed troubling images of wounded, tortured, bloodied bodies along the path one took through the pavilion, a reminder that artists' materials often hide the intensity of their subject matter, linking Hirschhorn to both Goya and Manet. In his remarks to the press, the artist emphasized the necessity of panic in art, and you really did come away feeling that he had thought deeply about many things, but waited until about six hours before the opening to start madly taping them all together!

Tomorrow: the Arsenale and curator Bice Curiger's vision of the contemporary art field entitled ILLUMInations.

Marjorie Och and Preston Thayer reporting from Venice.